Hingham Land Conservation Trust Fall Walk – October 14, 2017

by Don Kidston, Member, HLCT Board

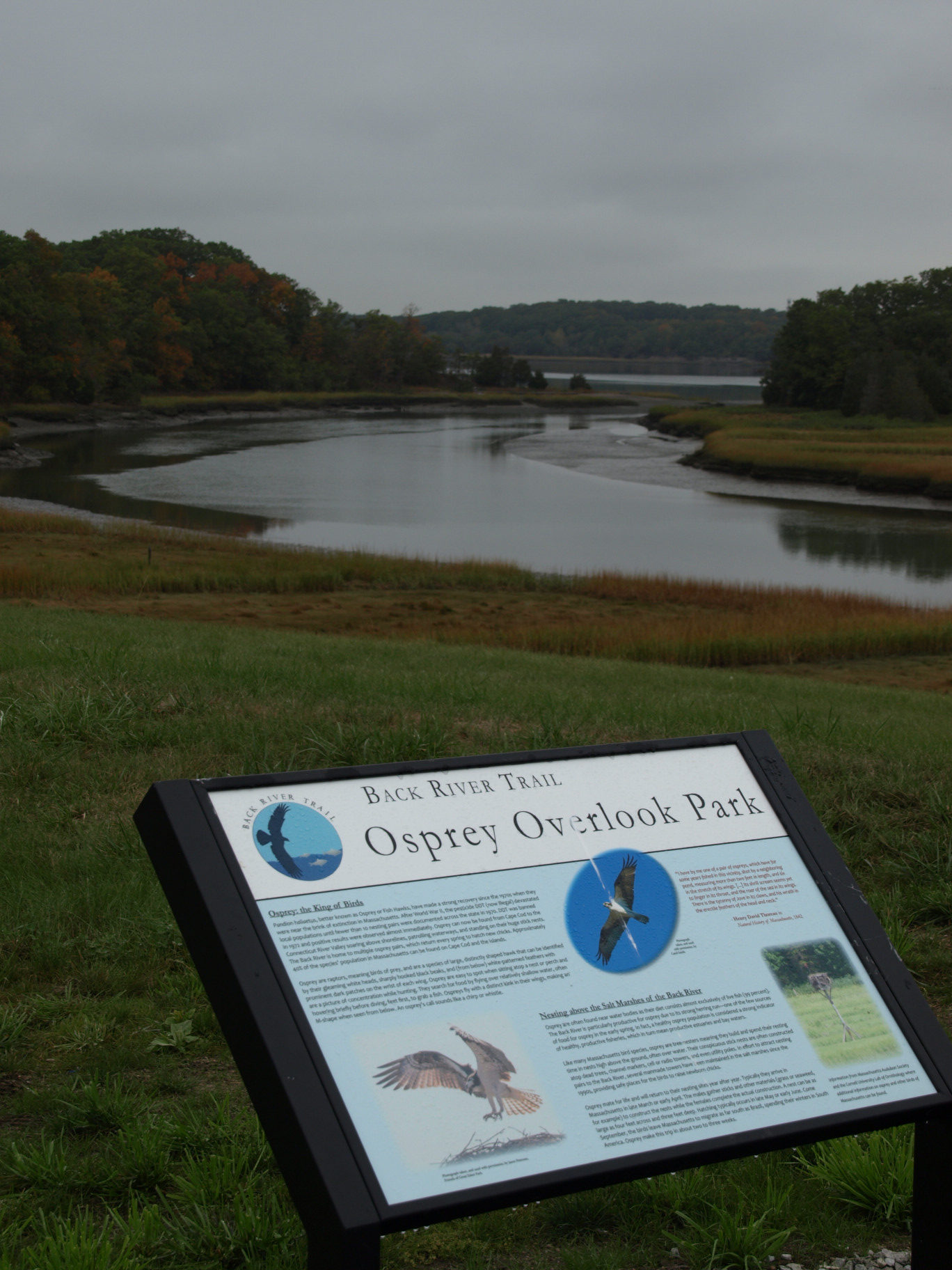

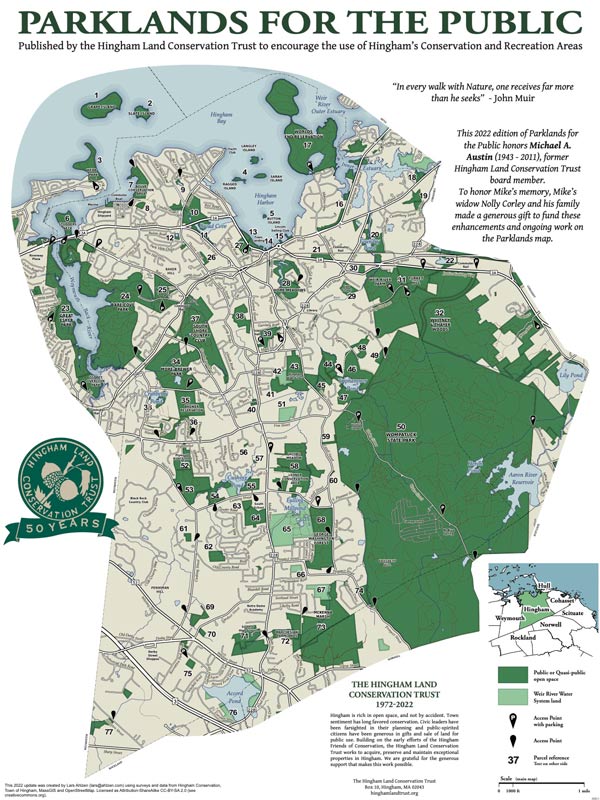

At 10:00 AM on an overcast misty morning approximately 45 participants met at the Osprey Overlook Park at the park’s entrance at the end of Wharf Street in Weymouth. Skip Hull, Hingham Land Conservation Trust’s Board Chair, greeted the attendees for the HLCT Fall Walk and provided a brief description of the new Osprey Overlook Park and the abutting Great Esker Park. He then introduced Andrew Hultin, the guide for the day’s walk. Andrew, a Program Coordinator for Weymouth’s Recreation Department, has a degree in environmental science and has spent almost ten years working on Weymouth’s Back River parklands.

Andrew described the history of the new park, pointing out a nearby incinerator which was in operation for about ten years beginning in the 1960s. He also noted the adjacent transfer station, which operated into the 1990s and then closed. The capped landfill forms the Osprey Overlook Park, an extension of the Back River parklands. He pointed out that Osprey Overlook Park and Great Esker Park form much of the western bank of Back River, which extends about 2 miles from Hingham Bay to Jackson Square.

The walk began along a ¾ mile trail along the edge of a marshy area. Andrew noted that the estuary, or area of the river that is influenced by salty tide-water, extends inland to the crossing of the Greenbush Line train tracks at the East Weymouth Train Station. As an example of the impacts of salinity on vegetation he pointed out 2 types of grass, one standing and one lying flat, the difference being their tolerance to salt in the water.

Osprey populations were reduced by the use of DDT, which caused the egg shells to become fragile. Since DDT was banned, platforms such as those across the marsh were installed to encourage the Osprey’s return. Ospreys also nest in dead trees, which are scarce and sometimes on the ground. Andrew noted that Mass Audubon has been banding Osprey chicks since the 1990s to track the birds and further their recovery. As we reached the top of the hill near a trail into Great Esker Park, Andrew told the group that the Osprey, a migrating bird, had left the area in mid-September headed for South America. A fish-eating bird, the Osprey return around mid-March to feast on herring after their long journey. They are joined by egrets and in recent years by eagles. The eagle population is also increasing in New England, and one has shown up here very early in the spring, although it stays for only a brief period. Andrew noted that there are now about 4 Osprey pairs that spend the full season on the Back River, which is near what is sustainable in this environment.

The early spring attraction for the birds and their mid-March to early April feeding frenzy is the herring run. Andrew told us that there are two types of herring, one which lives in the ocean and one which goes inland to spawn. The spawning herring, returning from a winter as far south as the Carolinas, swim up the Back River and the Herring Brook fish ladder in Jackson Square to Whitman’s Pond. In addition, there are striped bass and other fish for the Osprey to feed on through the summer. Andrew pointed out that those wishing to boat on the Back River should be aware of the tides. Much of the river is completely drained at low tide.

Andrew described some of the recent history of the one and a half mile long Great Esker Park. During the world wars when Bare Cove Park was used as a munitions depot, Great Esker Park, with its 90 to 100-foot tall eskers was held by the Navy as a barrier to protect Weymouth from any potential explosions in the munitions storage area on the other side of the river. The only construction on the Weymouth side was a roadway used to patrol the area. In the 1960s when the military bases were decommissioned the property was made available to the local communities through the federal land to parks program. Acquisition of Great Esker Park met with initial opposition in Weymouth but was ultimately approved through the efforts of Weymouth citizen Mary Toomey.

Upon entering Great Esker Park, the group walked along an esker on the main road to a trail that continued up along the peak of the esker. Before we headed up the esker, Andrew described how the eskers were formed 10-12,000 years ago during the ice age. As the ice, which capped the glacier, melted, it formed streams under the glacier. As the streams flowed they eroded the soil below and deposited the soil along their banks. Over time the banks formed long steep eskers, which were left behind as the glaciers receded. At approximately 95 feet in height the eskers at Great Esker Park are believed to be the tallest remaining in North America and second in height to eskers in Siberia.

A small portion of walkers chose to continue along the flat land along the river. Those taking the esker route walked a narrow path through the trees, following the sometimes-steep incline up and down the esker. The payoff were the vistas of the sky/marsh/water landscape viewed from the top—beautiful despite the overcast skies.

At the west side of the esker we all crossed over a bridge built years ago by Boy Scouts (one of a few in the park) crossing a stream from a salt pond which flows into the Back River. Andrew noted that the pond is a feeding spot for birds.

The group then followed a paved roadway to the Overlook in Osprey Overlook Park for one final view of the Back River and its estuary. Andrew identified the points of access to the parks for those wishing to return for further exploration. In addition to Wharf Street there are entrances from Puritan Road by way of East Street, and Elva Road off Green Street. Andrew was thanked for his excellent job as a guide with a large round of applause before everyone left.